WiRM 4: The Practice of Risk Management

What does Risk Management mean in practice, in the real word?

In my previous post, I introduced the philosophy of Risk Management (capitalised to represent the method, the whole body of knowledge). I stated the goal of the enterprise (survival) and proposed two ‘laws’ of Risk Management.

Plenty more could be said about that topic, and we may do so another time. Today though, we swap the conceptual for the tangible to discuss Risk Management in practice: how are risks managed in the real world? How are they defined and measured? What tools and methods are used manage them? What outcomes are we trying to achieve?

The Practice of Risk Management

Risk Management in practice can be split into two high level categories: identification and management. We must have some way to define and identify the risks, and then we must find ways to manage them. We will elaborate on those tasks below, but first a few caveats.

The practice of Risk Management is not a small, neatly delineated topic. Managing risk in the real world requires different skillsets drawn from different fields of knowledge, and the tools it employs and the forms it takes are just as diverse.

I’d wager that Risk Management has been present in every aspect of every domain of human activity, since forever. Our Risk Management practices evolved in symbiosis with our normal human activities because they had to: we couldn’t have survived without them. We were managing risk without even being aware we were doing it, but that’s often the case.

There is Risk Management in everything from insurance premiums to manufacturing standards to personal hygiene to industry regulations to gambling, ‘prepping’, war, social taboos, and much else besides. Every building, every consumer product, every organisation, and even our personal relationships contain multiple layers of Risk Management, although we are mostly unaware of them.

Infinitely Infinite: The Risk Management of a Car

Consider a car. It has wing mirrors and headlamps to give the driver better visibility. It has seatbelts and airbags to protect the passengers if there is a collision. It has ‘crumple zones’ front and rear to dissipate the collision’s force. Each of these adaptations to the basic structure of a car was motivated by safety and necessity – not a mindset of scientific inquiry. They are all forms of Risk Management.

Now think about the components of the car: the engine, the chassis, the electrics, etc. Every individual piece, down to the last ball bearing, must have been manufactured in line with some minimum standards, as set by the industry’s regulators. This too is Risk Management. The seatbelt and airbag mechanisms – themselves forms of Risk Management – must be stress tested to ensure that they will function when they are most needed. Even the Risk Management is subject to Risk Management!

The environment in which the cars operate presents another layer with its own features and mechanisms. There are roads with markings, speed limits, signs, and traffic lights. There are roundabouts to smooth the traffic flow. We have rules of the road which must be learned before you have the legal right to drive. If the rules aren’t followed, then we have police to hold the guilty-parties to account. It’s all Risk Management.

But the Risk Management of a car doesn’t just protect our health when driving; it is a necessity which enables the whole automotive enterprise to function. Few people would take to the roads if there was no agreement on which side we would all drive. Fewer still would buy a car if they thought the engine might explode the first time it hit 20mph. We don’t have to think about these problems because we created a multi-layered, overlapping system of rules, responsibilities, checks, and processes which (if followed) keep driving safe while keeping the automobile industry viable.

The same is surely true for every other consumer product or device. Whatever it is, it will have internal and external Risk Management, layers upon layers of it, overlapping and intertwined, spreading into every part of the product’s supply chain. It is intrinsic and essential, both to the individual product and its eco-system. We are mostly unaware of it. That’s how it often is with good Risk Management.

Risk Identification

Risks are determined by goals. So the identification of risks begins at the outset of the project with the statement of the project’s goal: the reason it exists and the outcome is seeks to achieve. Whatever that project is and whatever the context, once you have settled on a goal, you must immediately turn your attention to the risks: what are they, where are they, and what could or should you do about them?

The best way to identify risks is to get all the right people in the same room at the same time for a game of ‘What if…?’. What if a key supplier was out of stock? What if industry regulation changes after the next election? What if an employee in our finance department is committing fraud? What if there was an extreme weather event and our factory’s water supply was shut off for a week? An early brainstorming session is usually the first step in the process.

We want to explore every possible fault, accident, oversight, undesirable event, and worst-case scenario. If it’s bad, if it scares us, and if it could happen, then we want to write it down so that we can build a plan for it. It's important that we get as many different perspectives on the problem as possible, so we need to include people with different backgrounds and skillsets, people who come from every part of the business. We want all bases covered.

Structural models (e.g. a nuclear reactor or an airplane) are very helpful because they make the risks easier to identify and they limit the range of options and potential outcomes. With a structural model we can work through each sub-system and mechanism, all the way down to the nuts and the bolts, and explore every possible way every component could fail. The structural model acts like a blueprint for risk, thereby streamlining the brainstorming process.

Contrast that with an economy or a financial market, where we don’t have these kinds of maps. We don’t understand how every component of the system works, the potential threats are not finite or even definable, and naturally, we are not so good at managing risk in these environments. Worse still, disasters in financial markets don’t necessarily lead to long-term structural improvements. Air travel is antifragile, but financial speculation is not.

Whatever tools and methods we us to identify our risks, once we have decided on our final list, we can begin to make attempts to measure, model, monitor, and prioritise them. Now we getting into the actual management of the risks, which we will continue below.

Risk Management

All Risk Management efforts fall into one of three categories: prevent, neutralise, mitigate.

To prevent the risk, we take steps to ensure that the risk event does not happen. If we are successful, then the risk is eliminated, thereby ensuring it cannot eliminate us. For example, if an asteroid was on a collision course with Earth, we could send up a rocket to push it off course (in theory at least). This would prevent the asteroid from hitting Earth, which would eliminate the threat and guarantee our survival.

If we can’t prevent the threat from materialising, we might be able to neutralise it. In this scenario, the risk event will still happen, but we will be unaffected by it. Returning to our previous example, the asteroid might burn up in our atmosphere and by the time it makes contact with Earth, it is no bigger than a chihuahua's head. In this case, the atmosphere functions as a layer of Risk Management which can neutralise these kinds of threats.

If we can’t prevent or neutralise the threat, then we have no choice but to protect ourselves from it. We try to mitigate its impact as best we can. If the same asteroid was definitely going to hit Earth, we would climb into our bunkers, batten down the hatches, and hope for the best. (Although if the asteroid was expected to wipe out 99% of human life, I think I might just head towards the impact site and enjoy the fireworks show.)

Here are a few more examples of this triplet in action…

Medicine

Prevent: abstinence before marriage will prevent sexually transmitted diseases

Neutralise: vaccination will neutralise the risk of diseases like smallpox, polio, and MMR

Mitigate: regular testing won’t prevent or neutralise the risk of cancer, but earlier detection can mitigate the potential harm

Financial Markets

Prevent: sell the asset to eliminate your exposure to it

Neutralise: hedge your exposure by entering an off-setting contract

Mitigate: add funds to your loss reserves or capital buffers

Epidemic Control

Prevent: find the pathogen ASAP and eliminate it before it becomes an epidemic

Neutralise: vaccinate the population (only possible at local level, not global)

Mitigate: use masks, social distancing, and expanded ICU capacity to limit the impact

Prevent > Neutralise > Mitigate

As you can probably tell, prevention is the highest form of Risk Management because to successfully prevent a risk is to eliminate the problem entirely. Not only do you ensure your survival – the ultimate goal - you preserve the status quo. Prevention can be thought of as convex (in counterfactual space) because there is no limit to the costs and resources it can save us. At the very least, prevention is robust, as it leaves everything unchanged, undisturbed, undamaged.

While prevention is the preferred goal of all Risk Management efforts, it won’t always be possible. At times, neutralisation will be a much cheaper and more convenient option. Mitigation is the point where Risk Management starts to become Disaster Management, so we’d rather avoid that altogether but, when the higher goals are unavailable, it becomes our best-case scenario.

So just as we need to be clear about which risks we are managing, we also need to be clear about what goals our Risk Management efforts can realistically achieve. Is this a risk we must prevent, or can we neutralise it? Or, is it a risk we need to manage at all? These issues are to be discussed in our initial brainstorming sessions.

Closing Thoughts

Risk Management in practice is all about planning and preparation: identifying risks and managing them, so that they don’t take you out.

Individual risks may come and go, but there will always be a risk profile to manage. Risk managers are always on the lookout for exceptions, oversights, gaps in our knowledge and systems (this is where our healthy paranoia serves us well), and then updating our strategy and tactics as we go. The environment is continually evolving, so the shape of the risk profile will be changing too, so the management of risk must be a continuous process.

In many ways, Risk Management in the context of contagious diseases is like a military engagement: we develop plans, do exercises to spot weaknesses, and drill responses so that everyone knows exactly what to do when we make contact with the enemy. We do as much of our resource allocation and decision-making as we can in advance, so that we have as much free headspace as possible when the engagement begins and the situation becomes more complex.

It’s a lot like doomsday prepping too. The prepper’s goal is survival no matter what Mother Nature throws their way. They stockpile key resources and make as many decisions as they can in advance, so that when the SHTF, they have all their pieces in place and they can hit the ground running.

Both the military and the preppers are quintessential risk managers: the environment is complex, anything can happen, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. Unsurprisingly, the behaviours are much the same: stockpiles of key resources, sharpening skills, always vigilant, never complacent.

It’s a long way from clinical medicine and lab science!

Perhaps it is no wonder that the word’s response to Covid-19 was such a catastrophe. It was led by medics and academics who have no training in, or even concept of, Risk Management. So there were no risk managers at the decision-making tables. No brainstorming sessions, few stockpiles of key resources, no lessons learned from exercises because there were so few exercises done, and a sluggish response to the outbreak for the same reason.

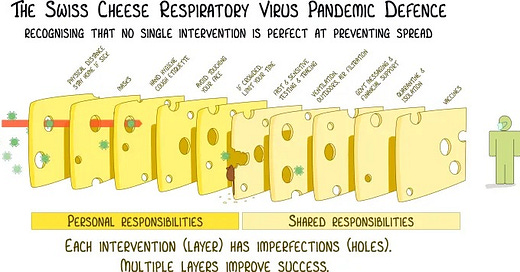

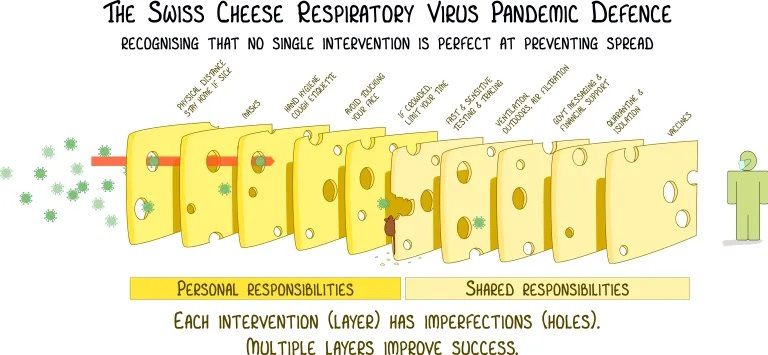

Instead, the world got a pandemic survival system which was explained to us as slices of Swiss cheese. It might as well have been made out of Swiss cheese, for all the good it did.